What if the Amish had the right idea all along?

How we can learn from the values-driven approach to innovation in an age of uncertainty.

I’ve been thinking a lot about uncertainty lately.

I just released a book all about the deep dread that took hold of the American psyche during the Great Depression…and what people did about it. The book is relentlessly upbeat and hopeful, which is something we could really use right now.

But relentlessly hopeful isn’t enough. Simply reminding people, we got through it before, we’ll be okay, isn’t reassuring. And why would it be? Those people and that time seem so different and so alien to us today. Things are moving sooooo fast. How could they possibly know what it’s like to live with all the world’s knowledge in your pocket?

I get it.

Historians, like me, need to do better.

That’s why I want to share the Amish perspective on technology. I promise; it’s not what you’re thinking.

But first, I need to make sure we’re all on the same page. I’m going to take a few minutes to summarize and crystalize the current mood. Until we all understand the problem, how would we know how to evaluate the right solution?

It won’t be an easy path, but then again, nothing worth having ever is.

Let’s go.

I could have picked on hundreds of so-called “thought leaders” in the media to help illustrate the zeitgeist, but I chose Tom Goodwin because (a) he’s generally not like this (catastrophizing to get clicks) and (b) he perfectly captures the general sense of foreboding. It’s sort of like the feeling Midwesterners get when the sky turns green on a summer afternoon.

That line about this all clearing up “in a few months” is Tom’s optimistic streak showing. I’m not sure I know many others who share that rosy outlook.

It’s natural to be worried when things seem out of your control.

Or how about Ted Gioia? I started following him while I was writing a history of the Roaring 20s, and his perspective on jazz history is without peer.

He believes we’re close to a complete collapse of the “knowledge system”—or more bluntly put, the technology-industrial complex. In his analysis, AI isn’t about to bring us the singularity, but rather, it’s a horseman of the tech apocalypse.

Here’s a short version of his 10 warning signs:

Scientific studies don’t replicate.

Public distrust of experts has reached an intensity never seen before.

The career path for knowledge workers is breaking down—and many only have unpaid student loans to show for their years of training and preparation.

Funding for science and tech research is disappearing in every sphere and sector.

Universities have lost their prestige, and have made enemies of their core constituencies.

Plagiarism is getting exposed at all levels from students to corporations—and all the way to Harvard's president. But the authorities just take it for granted.

AI is imposed everywhere as the new expert system. But when it hallucinates and generates ridiculous responses, the authorities (again) take this for granted.

Science and technology are increasingly used to manipulate and exploit, not serve.

Scandals are everywhere in the knowledge economy (Theranos, Sam Bankman-Fried, collapsing meme coins, COVID, etc).

We hear constant bickering about “fake science”—from all political and ideological stances. Nobody talks about “true science.”

I’d invite you to read the rest of it, though I might suggest you take it with glass of scotch. (You’ll need it.)

If I’m being honest, I’m not sure what to make of all this.

We’re clearly in a time of transition—I’ve studied several. Trust me. I know one when I see it. That’s the curse of studying history.

For some, the response is to buckle down and power through it. That always seemed like a recipe for cardiovascular disease to me, but you do you.

For others, the response involves grasping for false certainty—listening to any number of “influencers” or “leaders” or “movements” or “tribes” who will offer the illusion of clarity.

Some people trust in their faith—whatever that looks like for them—and surrender their fate to a higher power.

I’m certainly not here to cast judgement on any of those approaches, but simply to offer a perspective on a different one. It might be a technology perspective you hadn’t considered from a group of people you might never had thought to ask.

The Amish.

The common joke about the Amish and technology goes something like this:

In other words, the Amish are a relic—frozen in time somewhere around the mid-1800s—and stubbornly refuse to join the rest of us in our technology utopia.

Isn’t it funny, then, that on most measures that truly matter in our lives—longevity, cancer, obesity, life satisfaction, family, and faith—the proverbial Amish buggy leaves our 1.9-second 0-60 EV in the dust.

The real question becomes, why? Or more importantly, how?

To answer that, we need to clear up a myth about the Amish.

They are not anti-technology. They simply have very high standards for adopting it. Much higher than ours.

For every new piece of technology, the Amish experiment with it. They designate one or two families to adopt the technology and track what happens.

For example, when Amish adopted the automobile, they noticed that families with a car would travel much further away from the community to have a picnic or go for a hike, instead of staying closer to the community and sharing that experience with their neighbors.

Community is one of the Amish people’s core values.

There was nothing inherently sinful about the automobile; it simply led to outcomes that were contrary to their values. So, they rejected it.

Many Amish adopt computers—but not televisions—for that same reason. They’re just careful about how they use the tool. Computers have a lot going for them. Televisions, much less so.

I think what we really mean when we say we’re “uncertain” about the future is that we do not have a clear sense of our values.

Without a clear sense of the intrinsic value of art, who cares if DALL-E generates paintings?

Without a clear sense of the intrinsic value of writing, who cares if ChatGPT writes our emails?

Without a clear sense of the intrinsic value of human connection, who cares if Claude becomes our best friend?

But I believe people do have a sense for those things, even if they have trouble putting those thoughts into words.

I believe that disconnect and deeper search for true meaning is what’s driving this sense of dread and foreboding.

That’s one of the major lessons from my latest book about our response to the Great Depression: We reconnected with our values and made choices that were meaningful and enduring. Why do you think we call these people the “Greatest Generation?”

We can…should…must relearn their example.

At its core, the decision to adopt technology must be about values, not value.

Unlike our grandparents in the Great Depression, we don’t lack for resources—that’s what the information age has gifted us more than anything else—but we lack the practice using them.

We are philosophically flabby.

We need to get into shape.

Fast.

Here’s a humble first step to get yourself back to the values gym:

Pick one piece of technology you own, use, or rely on. Ask yourself: Does this technology bring me closer to what I value in life or take me further away? If the former, how do I ensure it doesn’t evolve into something I wouldn’t like? If the latter, how could I change it (or how I use it) to better align with my values?

And if the answer is “no,” have the courage to abandon it.

You’ll be better for it.

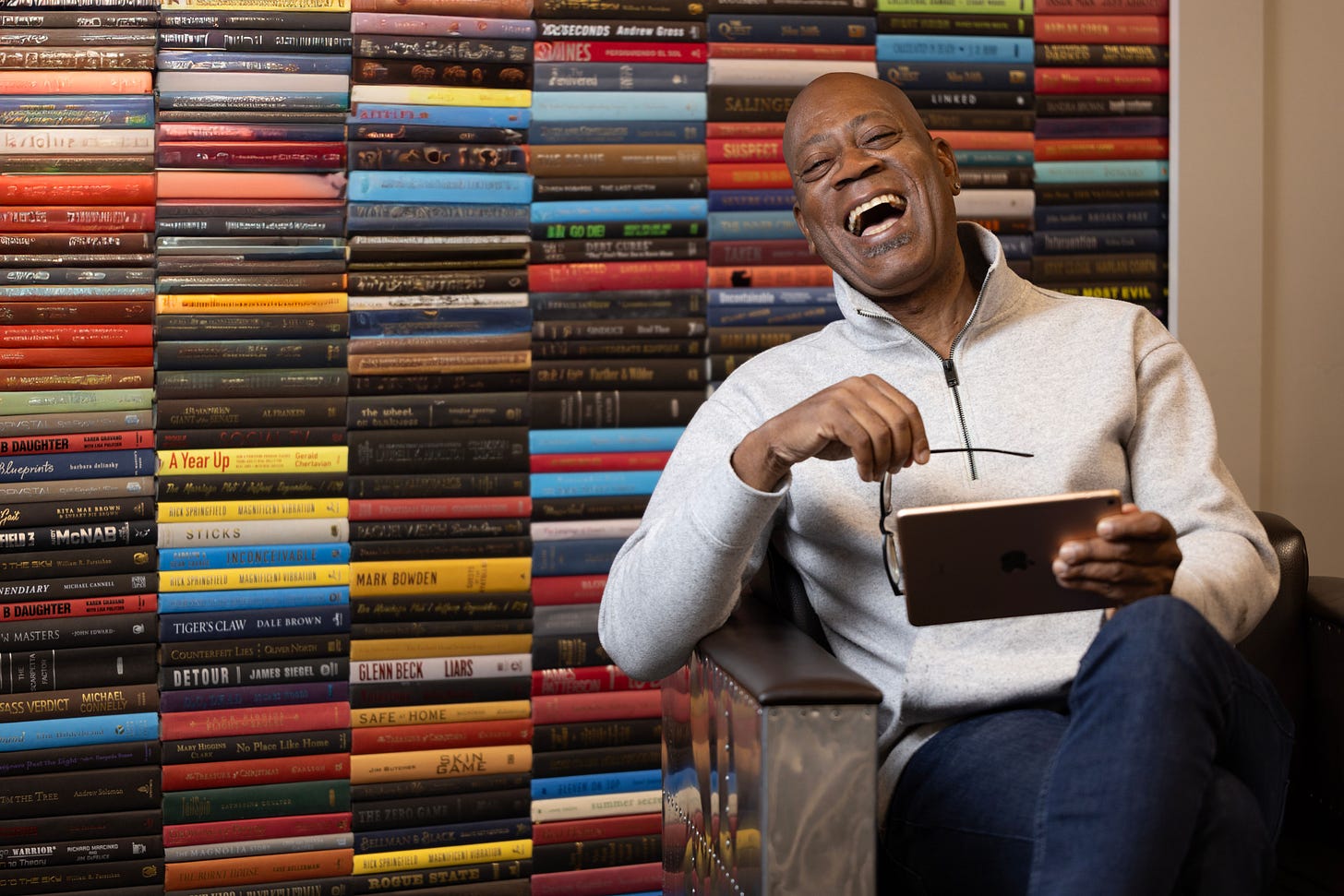

And one more thing: If there’s one person I follow who’s started a mental exercise regimen, it’s Diamond Michael Scott: The Chocolate Taoist™. Follow him.

This may well be my favorite post of yours of all time! It really does offer a way forward