How Rocky* reminds us to question assumptions

*No, not the Rocky you're thinking. A brief history of counting. And "Bullfrogs" are almost ready to hatch.

What aliens can teach us about counting…and the assumptions we never question.

Okay, I suppose it’s not much of a spoiler to tell you that in Andy Weir’s novel, Project Hail Mary, the Earth-based explorer encounters an alien from another star system trying to find answers to a mysterious life form “infecting” both of their stars. It’s a fascinating book, but this isn’t a book review. I want to choose a very specific example of a communication challenge the pair encountered early on. It’s an assumption most people have never questioned.

Why do we count to 10?

Is there something special about the number 10? Or multiples of 10? No. There’s not. This is an interesting historical question. So why do Arabic numbers use 0 through 10? Why are Roman numerals so similar? Why are Chinese systems similar? Or Mayan systems? Pretty much everywhere we run into number systems, even if the people never met each other, they use what scientists call “Base-10” systems.

Simple answer:

Makes sense, right?

But what if we didn’t have ten fingers?

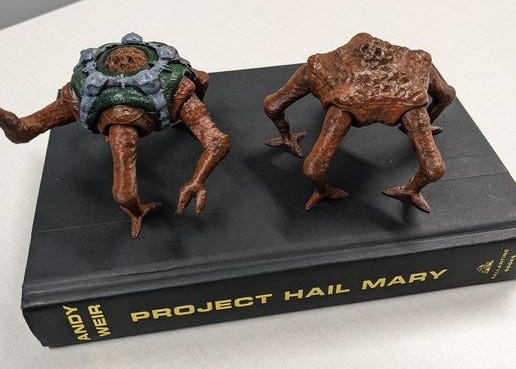

Do you notice something about Rocky in the photo? How many fingers does the alien have? Three per hand. With five legs (arms?), Rocky needs three of them to stand, leaving two appendages to count. It’s natural that all the counting systems on their planet would use Base-6 systems. Weir uses this to illustrate a basic point:

Counting serves a purpose.

By the way, there are lots of ways to count, all with different uses. And you’ve probably used some of them and never thought about how you effortlessly switched:

Unary: Draw a hash mark. That’s one. Draw another one. That’s two. Another one, three. You get the idea. You’ve certainly done this, right? (After four, you probably did a horizontal hash mark to indicate five.) It serves the purpose of counting better than using Arabic numbers when you don’t know how many of something you’ll end up with. It’s probably the first type of counting invented by humans.

Binary: This is how computers count—they take advantage of an “on” or “off” electrical current, so two states are all computers get to work with. In this system, 235 would be represented as 11101011. It’s a pain to count that way, but computers are fast.

Quantum States: Whoa boy, this gets weird. It’s important to think about though because (if Microsoft is to be believed, and I’m not certain they should), we’re a few years away from quantum computers. They take advantage of weird behaviors—as in, a quantum bit (or qubit) can be both zero and one at the same time. Or any of an infinite number of intermediate states. How the heck do you count that? Maybe it will have something to do with the “spin” properties of elementary particles or entanglement or even new materials, but dang. That’s going to get funky. (For example: Spins aren’t really “spinning” in the way you’re thinking, they represent a measure of angular momentum with fractional values: 0, 1/2, 1, 3/2, 2, etc. Yeah. Weird.)

Roman: If you lived in the Empire in 100 ACE, you were good at this. Otherwise, only people who follow Europe’s royal families and Catholic popes really care about Roman numerals. They’re sort of cool, but they’re not super useful otherwise. Why? No placeholders. The year 2025 in Roman numerals is written MMXXV. There’s no easy way to subtract 1995 (MCMXCV) using the system because the characters don’t line up. (Try it.) That’s why Arabic numerals (0-9) are sooooo important.

Speaking of the importance of Arabic numerals in a historical context. Did you know that it wasn’t until the 1500s or so that everyone got on board with them? Funny enough, it was one of the catalysts of the Age of Discovery and Scientific Revolution. Numbers are critical. Without a good number system, everything is harder—Navigation, Science, Engineering, Commerce. Try to do any of those things without numbers. Good luck.

By the way, animals count too—just in different ways. It’s obvious when you think about it; it’s a survival strategy. IMO, Honeybees are the most interesting. If you’re in for a good mind-bender, read this article in Quanta.

In short, even something as everyday as counting can be questioned. If you want to get better at innovation—creating new and useful things—you should get very used to questioning foundational assumptions. That’s where all the most groundbreaking discoveries are hiding.

And go read Project Hail Mary. You’ll like it.

Speaking of books…

Book update:

“Bullfrogs” is almost ready for preorder…

My latest book, this one focusing on innovation and consumer culture during the Great Depression, is in final editing and audio recording. I’ve learned to do those two at the same time—recording the audiobook is a great way to catch obvious errors that slip through both human and AI copyeditors.

When will it be ready for preorder? Probably in the next few weeks. I’ll send out an announcement when I feel confident in the release date. I’m hoping to have all three versions ready for preorder at the same time—paperback, ebook, and audiobook—so you’ll be able to get the format you like best.

Stay tuned.

In the meantime…

Here’s the pitch for the book:

Necessity is the Mother of Invention

How did we get here? Whether pondering the latest tech disruption, political crisis, or cultural drama, it’s the question we as Americans find ourselves asking more and more. “Learn from history,” they say! But most books are so dry that you feel like you’re the one aging. TV is a non-stop red-team/blue-team cage match. Podcasts require sifting the who’s whos from the yahoos.

History shouldn’t be just a tale of two opinions.

Get the story behind the history with Jason Voiovich’s new book, Bullfrogs, Bingo, and the Little House on the Prairie: How Innovators of the Great Depression Made the Best of the Worst of Times.

Go beyond well-known events like The Dust Bowl into the lesser-known changes that built modern America. Why were bullfrog farms popular backyard businesses? How did Al Capone change law enforcement? When did dogs become part of our families? Jason’s “tapas menu” take on the 1930s shows that bad times create the most surprising outcomes. It’s more This American Life and less college textbook, helping you find the answers to “How did we get here?” so that you can decide “Where do we go from here?”

Learn why the Great Depression is the most misunderstood decade in American history. Preorders will be available soon.

Like it? I do.

I got help from the Startup Hypeman himself, Rajiv ‘RajNATION’ Nathan, to make this pitch sing. If you’ve got a startup, you should get to know him.

One last thing…

If you’re interested in being an early reader and joining the Jaywalkers (that’s what I’m calling my reader group), shoot me a line! I’ll hook you up.