Hype Storm

It may feel like the end of the world as we know it, but if history is any guide, you should feel fine.

A public service announcement from your friendly neighborhood innovation historian. Send this to anyone you know who’s freaking out about what they’re seeing (or not seeing) in today’s media.

As some of you may know, my wife and I recently relocated to Southwest Florida. Of all the places you could choose to move to in the United States, Naples has to be in the top ten. After a lifetime of frozen tundra, living somewhere that never dipped below 50 degrees and was only a few minutes from a white sand beach held a certain appeal.

However, as a certain 1980s crooner reminds us, every rose has its thorn. Our thorns are shaped like hurricanes.

After watching Debbie and Helene only brush past South Florida, Milton looked more ominous. The weekend before landfall, we packed up my wife’s parents and flew everyone back to Minneapolis to ride out the storm. And heck, we might do a little leaf-peeping, Honey Crisping, and Oktoberfesting while we were there. This is the perfect time of year to visit Minnesota. We should know.

It’s a three-and-a-half-hour direct flight from RSW to MSP, and everyone seemed relieved to be in the air. (The terminal was a stressful place that morning.)

About 90 minutes in, my bladder reminded me that I drank a giant cup of coffee at the gate. Walking to the back of the Boeing 737-900, I noticed more than half of the passengers intently watching their setback screens. Watching wasn’t unusual, but the intensity was strange. No matter. I had…other things on my mind. On my way back, however, I understood what all the fuss was about.

At least half the screens were tuned to live CNN coverage of the impending hurricane, and every single one of them featured a lower-third graphic overlay of Tampa mayor Jane Castor telling her constituents, “YOU’RE GONNA DIE.”

Of course, context matters.

Just as in retail, hurricane risk is all about location, location, location. Every area in Florida is assigned an evacuation zone: A through F. As and Bs better run for it—they’re on the coast, near a river, or close enough to be impacted by storm surge. It’s storm surges and flooding that claim the most lives.

Es and Fs? It’s not as big of a deal for them. They’re well inland. (We're an E. We lost power for a handful of minutes. That’s it. I checked on our power company’s online monitoring service.)

However, the mayor didn’t want to be misinterpreted or taken lightly. Her constituents—at least some of them—were in mortal danger. Tampa expected a 12-to-15-foot storm surge. You’re not swimming your way out of that. It was better to risk overstating the risk for most to ensure those who needed to hear it got the message.

But CNN wasn’t broadcasting to Tampa. CNN was broadcasting nationwide. The 99.99 percent of the viewing audience who didn’t have that context, especially those who had grown up in the era of three networks and Walter Cronkite, were losing their collective shit.

What was the reaction of Xers and Millennials on the plane? It was an early flight. Most of them were asleep or reading a book. They knew how to interpret the hyperbole they saw on 24-hour news networks. (That’s a theme we’ll come back to later.)

Many of us were watching this guy instead:

The National Hurricane Center published updates on YouTube twice daily. It was fact-based, short (six to seven minutes), and his polo shirt with the NHC logo was clearly not chosen for its sex appeal. He wasn’t a “personality;” he was a scientist. The broadcast had everything you needed to know. It was urgent but not apocalyptic. He didn’t cut to some dumbass standing out on the beach in a windbreaker “reporting live.” He simply told you how it was going to be.

Most other “journalists” simply pilfered their facts from these reports. For the Xers and Millenials, why not just listen to an actually authoritative source? We’ve had enough of “influencers.”

Sadly, this experience is not unique.

In the past few years, especially in the last few months, I haven’t met anyone who thought the media was doing a good job. Sure, we can point to great local television journalists, independent researchers who moved to Substack, or (sadly, all too often) someone who shouts the loudest for “Red Team” or “Blue Team.” However, on the whole, only 32% of Americans say they trust the mass media “a great deal” or “a fair amount” to report the news in a full, fair and accurate way.

We like to harken back to a magical time when the media called it like it was, when we all agreed on “the facts,” and when opinions were relegated to the opinion page.

I’m here to tell you that was never true. Those who remember the halcyon days of “only three channels” and that “there was no such thing as misinformation” are misremembering.

To help us understand where we are today, it’s helpful to understand the role of innovation and technology in shaping the media landscape, which is a much longer arc of history than (notably faulty) living memory.

That’s especially important now.

As we prepare for another raucous US presidential election, it’s time to step back and relax. Most people aren’t as dumb as you think they are—even if they’re on the “other side.” (By the way, they’re likely to believe you’re a moron as well.) Not only is the mass media not an accurate reflection of reality, neither is social media. Remember that only 10% of people are responsible for 90% of the content...and only a fraction of the population is even on social media. Weirdos are noisy, but they’re a fraction of a fraction of a fraction. Relax. Your neighbor is probably cool.

Simply put, media (traditional or social) doesn’t operate as most people believe.

Media is a business. Their business is not truth; it’s attention. It always has been.

How often will you tune into a broadcast that tells you, “Hey, everything’s pretty good, but there are some things we really should pay attention to soon.” Not very. Even if that’s the truth most of the time.

As we just saw on CNN, if it bleeds, it leads. Or even simpler: Hype sells.

Yes, we’ve seen a lot of new media recently that didn’t exist when I grew up in the 1970s and 1980s. But that’s not more than what Americans faced from the 1880s to the 1950s—telegraphs, newspapers, magazines, cameras, radio, telephones, movies, and television. Seriously. Compared to that, TikTok is just a short-form YouTube, which is just television on a computer.

Every generation has struggled…and then they figured it out. They learned, adapted, and became better media consumers.

We’ll be fine.

You will be fine.

Don’t believe me?

Let’s explore a little perspective. Don’t worry. I’ll keep the history lesson brief, relevant, and reassuring.

Printing Press (1440)

Most people who grew up in a Christian household know the story of Martin Luther and his ninety-five theses in 1517. Luther's goal was to force an academic discussion within the Catholic Church in Europe about its abuses, especially the purchase of so-called “indulgences”—basically, get-out-of-Hell-free cards.

What most people don’t know is that his ideas were anything but new. They had been circulating for decades. Until then, Papal authorities could squelch dissent because it could never spread that far. But Luther had access to a printing press, and that changed everything.

Before the printing press, ideas could spread only so far as people could carry them. Eliminate the people, and you can often eliminate the idea—or at least slow it down considerably and give yourself time to react. After the printing press, ideas became tangible things in their own right. They have become powerful in a way that’s hard to describe. Books were the first mass media, and there’s a good argument that they created the modern world. To the authority figures of the day, books were dangerous.

For all the conflict wrought by the mass availability of books and the ideas they contain, would we want to return to a world without them? I would say not.

Newspaper (1605)

It should come as no surprise that the first newspaper generally recognized as such hails from Germany. The printing press was invented there, and the Germans enthusiastically embraced it to create a new form of mass media—shorter than a book but with more timely information.

What’s important to remember is that while producing books required extensive research, great skill, and expensive production, a newspaper (or pamphlet) could spread ideas much more quickly. More to the point, nearly anyone could do it. Pamphlets and newspapers played a critical role in the lead-up to the American war for independence, as just one example of many. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Patrick Henry, and James Madison used short-form publications to rush their ideas to market. Instead of months, new writings could appear in just days. More importantly, they could respond more quickly to how their publications were received, building on arguments and adjusting messages through multiple pamphlets.

Unsaid explicitly (but implied in context) in that description is that newspapers and pamphlets had a point of view. They were not unbiased sources of information. That was never the idea. In fact, you only see a “truth-focused” investigative journalistic approach in response to the so-called “Yellow Journalism” era in the early 1900s. Before then, all newspapers were biased. In many ways, today, we’re simply headed back to the future.

For all the accusations of bias in newspapers (much of it justified), would we want to return to a world without them? I would say not.

Electric Telegraph (1816)

Think of it for a moment. Before the telegraph, the fastest way a complex message could get from point A to point B was as fast as a human (or sometimes, an animal, like a passenger pigeon or horse) could carry it. When you read history before this era, you must continually remind yourself that messages could take days, weeks, or even months to arrive—if they arrived at all. The telegraph changed all that. Now, operators could send messages by opening and closing an electric circuit. That’s the entire idea behind the dots and dashes of Morse code, though that wasn’t the only system.

Technology is fascinating, but it is more applicable to our purposes because of how it has changed the nature of communication. During the Civil War in the United States, journalists would send messages from (near) the front lines to their editors in far-away cities. These dispatches could be published in newspapers as soon as the next edition was ready. However, the speed and risk inherent in the transmission changed the way information was packaged. The signal could not get through if a telegraph line was cut—a real possibility in a war zone. This forced writers to communicate the most critical information first, with details following in descending order of importance. This is the so-called “inverted pyramid” style of journalism that still dominates today.

More than any other technology, the telegraph changed the nature of storytelling from beginning-middle-end to end, a little middle, and probably no time for beginning. Communication became faster and more urgent, but often carried less context and meaning. We may not use telegraphs any longer, but the idea remains embedded in many other forms of mass media.

Despite the occasional lack of background and context, would we want to return to a world without high-speed communication? I would say not.

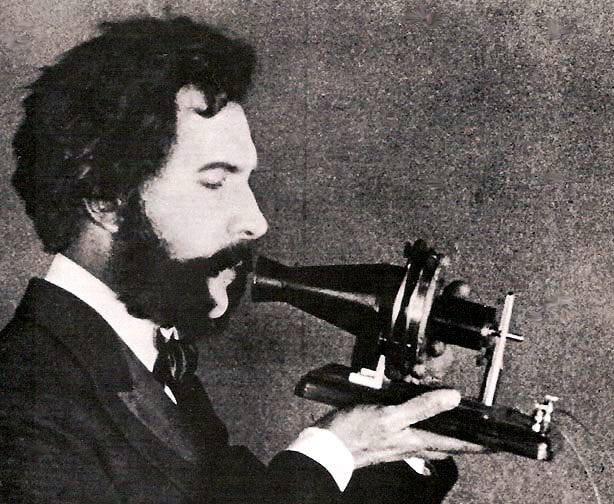

Telephone (1876)

There were two big problems with the telegraph. First, it could carry only text-based messages. As we know from modern communication, text-only can lead to miscommunication and misinterpretation. That meant most telegraph messages were clear to the point of bluntness or written in prearranged code that only the sender and receiver could understand. Second, they were asynchronous—in other words, only one message could be sent at a time. It was faster than writing a letter, but certainly not “real-time” two-way communication as we understand it today.

The telephone was the first live communication method that could connect any two people (or a small group of people) with the sound of their voice, complete with inflection, tone, and emotion. Think about what that meant. Remember that before this time, if someone moved…say, across the country…you may not only never see them again, but you may never hear their voice again. The telephone connected people in a personal way over a distance that simply was unimaginable before. It was the first truly social network. There’s something about hearing another human’s voice that, quite figuratively and literally, speaks to us.

Despite the interruptions, pointless calls, and telemarketers, would we want to return to the days when we couldn’t communicate with someone live? I would say not.

Camera (1888)

The idea behind the camera predates the modern era, but what we’re talking about here are the first reasonably priced, commercially available film cameras manufactured by Eastman Kodak. Before George Eastman, you (nearly) needed college degrees in chemistry, optics, and mechanical engineering to get a good photo. Kodak simplified the process and mass-marketed the cameras with the slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest.”

I’ve devoted a chapter in my upcoming book on consumer culture in the Great Depression to color photography, but the profound change had already taken off. Newspapers were among the first to use photography as a mass media tool to help tell stories, but it was magazines that elevated photography as its own mass media art form. Glossy, captivating photos could show what a description could not. In just one practical example, photography essentially created the mass tourism industry. Why? Pretty easy. Once you saw a photo of Yosemite or the Grand Canyon, you wanted to go. And like the radio (which we’ll talk about next), photos were accessible to be consumed by anyone, no matter their age, education level, or language.

Despite how images can manipulate our perception of the world, would we choose to return to a world without images? Would you remove the camera app on your smartphone? I would say not.

Radio (1894)

Radio (along with the telephone and telegraph) were the first mass media that didn’t require the listener to know how to read.

That’s a simple statement, but it’s utterly mind-blowing when you think about it. We take literacy for granted today, but that certainly wasn’t the case in the late 1800s. Before then, the number of people who could participate in media was limited to those with a high education level. That was more than it was in the days before books, but only a fraction of the population could read and write proficiently. Broadcast radio democratized mass communication in a way other media could not. (Telephones and telegraphs were point to point.)

What’s probably just as important is how radio changed the business model of mass communication. Until that point, the recipient, subscriber, or reader paid for access to the communication material—you bought a book, a newspaper, or a telegraph message. But that didn’t work with radio. You needed special receiving equipment (the “radio” box) to listen, but after you bought one, how would the broadcaster (a new term) know who was listening in order to charge them? The solution was obvious, and we still live with its consequences: advertising. Businesses that want to sell products and services will pay to sponsor programming or run commercials on radio stations whose audiences match their potential customers. As the radio listener, you don’t pay. Subscription services have only made a comeback in the past 15 years but are still only a portion of the overall radio market. Free sells.

Despite all the ads—some good, some bad—would you like to pay every time you engage with media? Most people are okay with a few ads if they get their entertainment for free.

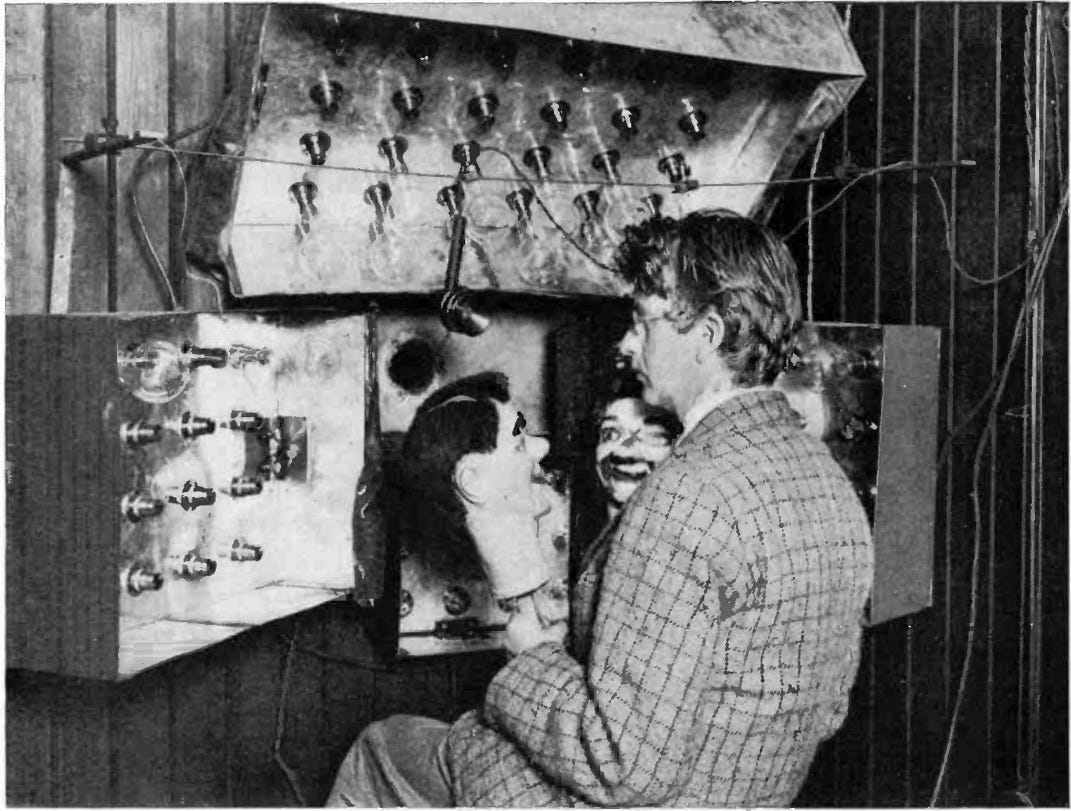

Television (1928)

Television didn’t come into its own until the 1950s. The three major networks—ABC, CBS, and NBC—were natural outgrowths of the radio conglomerates of the time. That’s critical because they took their advertising business model and affiliate networks with them. In other words, all local stations were affiliated with (and dependent on) the national broadcasters for much of their programming, and all of them relied on advertising for their revenue. What’s more, government regulators restricted competition for limited broadcast spectrum.

This constrained environment created the “everything was great, and everyone agreed” misremembering of the Leave It To Beaver era of journalism. It’s not that everyone agreed, it’s that the “Overton Window” (what topics would be discussed) was very small. When there are only three networks, and all are afraid to lose ad revenue to a basically-the-same competitor with the same reach and audience, network executives were loathe to discuss anything that might alienate the moneymaker.

That would all change with deregulation and cable news in the 1980s. We’ll touch on that soon enough, but for good and for bad, the media landscape could expand to better represent the actual diversity of viewpoints, not simply an artificially limited one.

Despite the batshit crazy stuff you can see on cable television these days (when was the last time the History Channel showed a “history” show?), do you really want to go back to the days when only three old white men told you what to think? I would say not.

If you’re this far in, I suspect you may not (yet) feel reassured.

Since television became popular in the 1950s, we have seen an explosion in media options and formats. There are so many more screens now, especially ones we carry in our pockets. But I would argue that you have everything you need to know and all the tools to become a savvy media consumer.

There’s no arguing that we have more media today than we did 50 years ago, but I’m not sure they’re fundamentally any different.

Let’s run through some of the ones people ask me about when we have this conversation:

AM Talk Radio: Haven’t Firebrands taken over talk radio and poisoned our public dialog since the 1980s? There have been firebrands on the radio since the 1930s. Look up Father Coughlin if you want to learn more. We survived.

24-Hour Cable News: Founded by Ted Turner in 1981 (Fox and MSNBC were founded in the mid-1990s), CNN’s “innovation” was filling 24 hours with “news” programming. They quickly figured out the news was hard. Opinion and commentary are easy and cheap. It’s the same thing Time magazine learned in 1926.

Craigslist: In 1996, this web-based classified ad service cut out the newspaper middleman, singlehandedly removing a major revenue stream from print newspapers. As a result, local newspapers were gutted. Most have closed in the past 20 years. But relying on classified ads was a lazy business model. I say “lazy” because it disconnected the value of local news from the act of paying for it. Many people say they want local news, but if they’re unwilling to pony up, they don’t really want what local news was selling. That’s Marketing 101. Newer providers are filling the gap…quite well, actually. It’ll be better, but it may take a little while to sort out.

Google: is just a fancy library. ChatGPT is just a fancy (but less good) librarian. We’ve had libraries for a looooong time. I’m not discounting easy access to information, but it’s not a new idea. In fact, there’s an argument that the “authority” based organizational scheme Google uses (what’s important is what the group thinks is important) isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Wikipedia is a good example of an alternative structure without as many of Google’s shortcomings.

Email: is a cheaper, easier telegraph. Same with instant messaging.

Blogs: are just electronic pamphlets. Benjamin Franklin would have recognized them.

Message Boards, like Reddit: are just electronic town squares. Julius Caesar would have recognized them.

Facebook: Pre-agricultural societies would have recognized social media, at least the idea behind it: Keep in touch with your tribal companions. Social media allows you to choose a group you wouldn’t ordinarily meet while gathering berries or hunting mammoths. That’s neat, but it’s not a new idea.

YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram: are just fancy televisions and cameras.

But wait! There’s more! What about artificial intelligence? What about the algorithms that underpin many of these technologies—the unseen software that manipulates what we see and how we react?!

We used to call those algorithms editors. People felt the same way about the outsized influence of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer as they do today about Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, and Sam Altman. Instead of smoky rooms, now it’s geeky basements. Instead of whisky and mustache twirling, now it’s Red Bull and code.

However, when you look beyond the supposed “command and control” of media, you notice something very different. To paraphrase a more well-known saying:

The arc of media history is long, but it bends towards access.

The history of innovation in media is a 500-year march towards giving more people access to ideas, making it easier to spread them, and democratizing the means of production. During all that time, pundits and elites wrung their hands that the hoi polloi simply couldn’t handle it. Sure, I can handle it, but my neighbor can’t.

Relax, you’re probably both wrong.

My advice over the next few weeks?

Turn off the TV. Put down the smartphone. Go for a walk. Meet your neighbor. Pet a dog.

We’ll be fine.

I've talked about this sort of thing before...as in, eight years ago. I think it's funny how little we often choose to learn. Here's a link to that interview: https://open.spotify.com/episode/6vHb89f0jMyzRF6LdKc1i8?si=37cc1eef2a1447e6&nd=1&dlsi=3e06e07b08054106