Chapter 1: A Big Fat Greek Marketing Lesson

Relearning how to learn from standup comics.

Over the course of my career, I’ve seen the amount of data available to marketing explode. We used to be content with once-a-decade US Census data, quarterly Nielsen reports, and annual readership subscription media kits. No longer. We still use all those tools (and their updated, online versions), but we’ve added so much more. Modern customer relationship management (CRM) and enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems provide up-to-the-minute internal data; the only restriction is your access level. Outside the company, we rely on excellent tools from Google, among many others, to dissect website analytics and search trends.

However, the increase in data hasn’t come with an increase in insight. Data has become a commodity, much like fast food for the mind. One day, sophisticated learning algorithms might make analysis a commodity as well, but I doubt it. Algorithms are programmed by people, and people have biases. Those biases turn into code, and the code leads to false conclusions. False conclusions diminish our trust in the original data. In other words, I’ll believe it when I see it.

What can’t be commoditized is our capacity to learn—to combine disparate pieces of information into something new and novel. I can’t say I want to go back to the days of paper census data, but simply adding more data without context is like overwatering the grapes and making bad wine. Data comes so fast and in such volume that we can’t possibly focus our attention in the right places. It’s time to relearn how to learn. As it turns out, there’s no better place to do that than on stage.

I didn’t go to the comedy club that Sunday night expecting to learn anything. I simply needed some time off. At least, that’s what my wife said. After politely listening to me carry on about work, she had the good sense to suggest we take our mind off things. Like most Norwegian women, she seems to have a knack for diffusing tension.

After I turned down about a half-dozen suggestions, we settled on Rick Bronson’s House of Comedy at the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota. In full disclosure, I’m not a comedy club guy, but I had the good sense to know when to say yes. Like most Midwestern men, I have a knack for recognizing a good idea when I hear one, especially when it comes from my wife.

The headliner that night was Angelo Tsarouchas (pronounced zah-ROO-kas), a Greek-born comic known for a bit of a raw style. I watched his highlight reel on before we left for the show. He was funny. I admit, he reminded me of my dad. Tsarouchas is a big guy with the friendly face and bear-hug personality I’ve experienced with other Greek friends and colleagues. I still couldn’t say I was excited about going, but I needed the distraction. This was as good as any.

We arrived at the club early, ordered a drink, and took our seats near the edge of the stage. The club featured thirty or so tables, a low ceiling, and good acoustics. Aside from five people chatting intently in the back corner, my wife and I were alone. I couldn’t help but eavesdrop. Of the five, I recognized Tsarouchas right away. One other I remembered from the Comedy Club website: He was one of the managers. I had no idea who the other three were, but I could easily overhear them talking about the night.

They weren’t telling jokes, if that’s what you were thinking. They discussed the likely crowd, checked sound equipment, coordinated routines, and gave each other advice. They all scribbled notes, Tsarouchas included. They took notice of new groups of people coming in—some confirming their suspicions, others clearly challenging their thinking. To me, it seemed like a sort of game.

It took another thirty minutes before the club peaked out at 60 percent capacity. The crowd skewed mostly older; forty- to fifty-somethings were the norm. When showtime came, it turned out there were three warm-up acts, each of whom I’d seen before in the back of the room. They were shaky, but perhaps they were trying to get their start. Then it was Tsarouchas’ turn. He ran through some of the material I’d seen online, but he made several adjustments. He played to the local crowd a bit but steered clear of some of his rowdier jokes, inserting different material so seamlessly I wouldn’t have known the difference if I hadn’t watched his other routines.

Then it dawned on me: I was watching an agile learning process in real time. Tsarouchas knew his material well enough to adjust on the fly based on the unique situation he faced. The other comics were helping each other to learn the same skill.

I’d never seen anything quite like it. I’ve worked with some of the brightest marketing and research professionals in the world, and we never got close to the level of precision and live adjustment those four standup comics displayed in a half-empty club on a Sunday night in suburban Minnesota.

That got me thinking. Marketing professionals brag about this type of adjustment all the time, but we rarely do it. These comedians were better than we were. Much better. To them, it was natural. The experience was humbling.

I suppose it’s time I admitted the real reason I was at the club that night. I wasn’t having an issue at work, I was having an issue with work.

I’ve been at this more than twenty years, about half in advertising agencies and the other half as a corporate marketing leader. I’ve seen both sides of the fence. Let me tell you, the grass can be brown on either side.

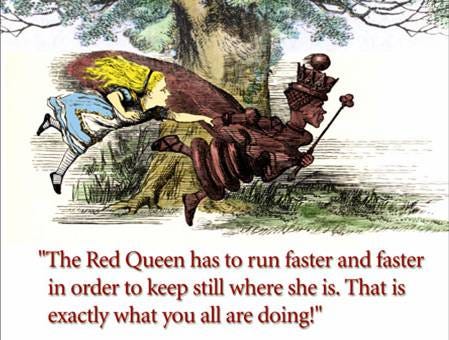

When I became frustrated in 2009, I jumped at the opportunity to attend the best graduate program for advertising professionals in the country at the University of Minnesota. When that wasn’t enough, I cajoled my employer at the time to put me on a plane to Cambridge to learn data science at MIT. Nothing worked. The more I learned about marketing, the more I understood how much we don’t know. I felt like the Red Queen in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, running faster and faster just to stay in the same place.

It was terrifying. I felt like a fraud. I walked into the club that Sunday night with deep and real doubts about continuing a career in marketing.

Tsarouchas, whether he knew it or not, executed a near-flawless marketing plan that night. He knew his material. He read the audience. He adjusted. He got the outcome he wanted (we were entertained), and at the same time achieved the outcome for the club (we would likely come back another night). What he did might seem a bit ordinary—of course, a touring comic would know how to work a room—but trust me, from a marketing perspective, there were dozens of ways this could’ve gone wrong.

He had no idea who would come into the club that night. Would it be a bachelorette party or a corporate outing? Would most seats remain empty, or would it be standing room only? Would the warm-up acts kill or bomb? Any of these variables would dramatically change the audience experience, and there was precious little Tsarouchas could do to anticipate it. The club owner might have a sense of the typical Sunday night crowd, but the unique cocktail of crowd dynamics, the amount of liquor consumption, and the performance or underperformance of the warm-up acts—not to mention what might have happened in the news that day—would present a scenario in which no amount of advance information would help. The situation was simply too unpredictable, too human. Tsarouchas had to adjust in real time as the evidence presented itself.

We marketing professionals talk a good game about “agility” and “responding to data,” but Tsarouchas forced me to ask myself some tough questions: How good are we? More to the point, are we as good as he is? If we claim to understand this concept so well, why aren’t we better at it in practice?

On the path to Rehumanizing Marketing, relearning how to learn had to be the first step.

The more I learned about how comedians ply their craft, the more I understood the depth of their challenge: Making people laugh, consistently, for thirty to sixty minutes at a time, is extraordinarily difficult.

We all have “funny” friends. They can crack a few jokes, make perfectly timed witty observations, and seem to be able to keep a room entertained for the entire night. However, let’s look a little closer at our funny friend. His jokes kill because he knows us; he has the background necessary to tap into common experiences, nudging his punch lines with calls to inside jokes.

Contrast that with a day in the life of a working comic at any given club on any given night. It’s unlikely anyone knows each other. The audience might be socially lubricated, but everyone reacts differently to the influence of alcohol. The comic can’t count on any sort of common experience. Touring comics routinely find staunch conservatives in San Francisco, California and avowed socialists in Mobile, Alabama. The comic can’t take a break, she can’t divert attention, she can’t share the spotlight. All eyes are on her, and the expectation is clear: I paid for this, you’re here to make me laugh, and you’d better deliver.

Here’s their secret: There’s nothing funny about being a comic. Let’s look at a day in the life of an average working performer.

Our comic wakes up in a strange city in a second-rate hotel after a long night at the club. If she was lucky, she cajoled the club manager into springing for a better room. Many times, she’s out of luck. Tonight, she’ll run through the same material at the same club in front of a different audience, all part of a four-night stand. But until 8:00 pm, she has twelve hours to fill. By herself.

(The more I learned, the more I realized why so many comics are clinically depressed: They’re alone. A lot.)

She has a routine. Before breakfast, she reviews the recording of her performance the night before. In years past, she used a small tape recorder she placed on the stool next to her water glass on stage. She still uses it at some low-class clubs, but the better venues send her video recordings from multiple angles. She scours the recordings with notebook in hand. Does she need a better transition from the third to the fourth joke in the second set? The audience seemed to drop off, and she needed to resort to her closing material too early to bring them back. She didn’t lose this audience, but she vividly remembers the sound of crickets halfway through a routine last week and the polite applause at the end of twenty-five brutal minutes. She records the reactions and ideas in her notebook, ready to practice them in the mirror later in the day.

During a cheap breakfast, she switches gears. All comics need to work on new material, and that takes tremendous discipline. Only a few lines out of a hundred may ever make it to the stage, so she must keep writing.

Later that morning, a promising routine jumps out of an interaction she has with a barista. She takes a couple of hours to work it out—refining the roles, the lines, the timing, the punchline, the tag. (A “tag” is a short line delivered after the punchline to keep the laughs going.)

She spends the afternoon in front of a mirror, imagining the audience and delivering her act exactly as she will later that night. She notes her body language, facial expressions, the volume of her voice. Was that too much gesturing? Was the facial expression too subtle to be obvious in the back of a crowded room? If so, is the expression critical to the delivery?

Aside from the club manager, our comic is the first one at the club. Together, they review the previous night’s performance, her adjustment plans, and the crowd he expects. The warm-up acts begin arriving soon thereafter. They walk through their routines while the stage manager perfects lighting and AV. Two of the three warm-up acts immediately hit the bar. They’ll never make it, our comic silently laments. They don’t understand how much work this is. But the third . . . the third won’t leave her alone. She can’t stop asking questions, getting opinions, trying out new material on her. Irritating as it is, she knows she was in the same spot just a few short years ago.

As showtime approaches, the junior comics begin to get nervous. But our pro settles down. She’s watching the crowd, and she’ll pay close attention to the cannon fodder acts sent in ahead of her. She has contingency plans for contingency plans. She might not kill tonight, but she’s absolutely ready.

As I observed the surprisingly unfunny lives of touring comics, it became clear to me that simply scratching the surface of the idea wasn’t going to work. I needed to go beyond the ideas and observe the actions that generated the results. Three specific habits make all the difference.

The first is deep and deliberate practice. Touring comics are obsessed with improvement, and will use almost any downtime (hotel rooms, airplanes, or waiting rooms) as an opportunity to refine a punchline or craft a new storyline. As marketing professionals, we have those same opportunities. Instead of mindlessly scrolling through LinkedIn, for example, we can search deliberately and quantify our results. We all have the same 24 hours. Comics simply use theirs differently.

The second is live experimentation. Practicing a routine in the mirror only goes so far. If the joke doesn’t kill in front of a live audience, it needs work. No comic loves bombing, but they recognize that getting out of their comfort zone is critical to improving their craft. Again, it’s hard question time: How often do I stretch out of my comfort zone and attempt tactics I’m not sure will work? CEOs and clients pay lip service to the value of experimentation, but in truth, most of them only want to hear about experimentation in retrospect—in other words, after the experiment was successful. They don’t want to hear about the ten tries that failed spectacularly.

The third is constant refinement. Comics are the most at risk when they find a routine that works. More than one comic told me that successful acts breed laziness—it feels good when a joke works, or a routine kills. But all comedy has a shelf life. What worked with one audience in one town might not work in another. Or if it works, it might not work for very long. I think this is the aspect of the comedian’s practice marketing can relate to most. Audiences are smart—smarter than we give them credit for. What was an exciting and fresh only a few weeks ago is stale and expected today. Refinement is the yin to the experiment’s yang. But once we hit our numbers, we often stop asking how much better it could be. We don’t try to run up the score, and we should.

Ugh. This wasn’t going to be easy.

After trying to condense everything I learned, I couldn’t help but linger on a story from a touring comic. He was performing in a small bar thirty miles outside Mobile, Alabama. He walked in, looked around, and saw what he expected: a bunch of rednecks drinking cheap beer. Adjusting on the fly, he focused his routine on excoriating left-wing politics, entitled Millennials, and aggressive feminists.

And he bombed. Badly.

After the show, while he was nursing a drink at the bar, he struggled to understand what happened. These routines killed just a few hundred miles north. The gay bartender smiled and reminded him not to believe everything he read online. People aren’t always what you expect on first look.

I felt for the comic. If I’m honest with myself, I would’ve made the same judgment call, and I would’ve bombed. I wondered how many times my marketing strategy didn’t work simply because I misread the situation or accepted my biases at face value. I wasn’t sure I would be able to digest what I learned from the touring comics if I didn’t confront my own biases.

I needed to move on. This time, I would get help from a jury box.

Practical Advice: How to learn like a comedian.

Do this today: Put yourself out there.

Comedians may write incessantly and obsess in front of the mirror, but they find the most value in testing their material in front a live audience. Nothing else comes close. You can replicate that experience (and the associated benefits) in your own marketing practice, whether you work for a marketing agency or as part of a marketing department. All it takes is getting on the telephone. Select a customer from your database and arrange 15 minutes to get their feedback on your latest marketing effort. Avoid sending them materials in advance—you are attempting to replicate the “live” experience of seeing your marketing materials for the first time. Don’t worry about polish. Your customer will understand any lingering rough edges.

Once you’re on the phone, make your case. In other words, treat your marketing messaging (or new product feature, or pricing plan) as if it were a one-on-one sales experience, because that is precisely how your customer will experience it. What was their first impression? What were their exact words? What do they compare it to? Does it conjure positive or negative reactions? Or no reaction?

Don’t be discouraged if the first calls are a bit awkward. Most comedians cringe at their first amateur nights, but every one of them who made it pushed through those barriers and improved. What they learned—and you will learn as well—is to better calibrate the voice in your head with the voice of your audience. You will improve your intuition in a way that no amount of reviewing click statistics will give you.

So, go ahead. Make the first call. Don’t wait. You can do it.

Learn something new: Visit a comedy club (on a mission).

Even if you are a regular comedy club patron, after reading this chapter, visiting the club now will prove a different experience. Your mission is not only to enjoy the performance but also to learn for yourself the mechanics of “funny”. You’ll likely find multiple clubs nearby, almost always clustered in the city centers of major metro areas. For obvious reasons, avoid the seedy bar that puts on the occasional open mic night. You’re interested in how a functioning comedy club works. Struggling through amateur hour won’t teach you much.

Plan to arrive early, ideally as early as the club will allow. Buy your ticket, skip the bar, and find a chair in the corner of the club where you can observe the night’s preparations. (If possible, introduce yourself to the club owner or manager. You might get some additional insights.) Here’s what you’re looking for: When do the performers arrive? How do they prepare? Are they being recorded? Are they talking to the manager/patrons/amongst themselves prior to the show starting? What are they talking about? If they’ll let you, ask them yourself! What is their prep schedule? What are they looking for? How do they plan to adjust?

Once the show starts, take notes. How do you think the comedian is adjusting during the set? If there is more than one performer, how did the next one adjust? After the show, hang around. Ask how they think the show went. Ask what adjustments they made. Ask what they would do differently next time. What you are looking for isn’t what they do, but how they approach their craft. Once you’ve been to a few shows, you will find ways you can improve your own marketing planning and execution.

Transform your practice: Start your own club.

Many organizations start “customer advisory boards” with the best intentions. Most of the time, they die on the vine. People are busy, and advisory boards are no fun. The same goes with “focus groups” and sterile “customer research”. This is your chance to change that. Instead of a board that meets infrequently, with a set agenda, in a dry conference room, rent out an actual club or auditorium. Serve drinks and food. Bring in entertainment, perhaps from those comedy clubs you have been visiting. Invite a diverse group of customers and make it worth their while to attend by handing them cash as they walk in the door (they’ll get a chance to use it soon!)

Once you’ve filled the room, ditch the slide presentation and put on a real show. For example, if you’re creating a campaign for a new laundry detergent, show three different ads (or if the creative isn’t ready, have your marketing team act them out on stage). Consider the comedian as the emcee for the event to keep it upbeat and fun. When you’re done, ask them to buy the detergent from one of the three “teams” (you gave them money, right?) Who do they buy from? Why did they buy? Did they keep their money? Are they bored?

By putting your organization out there, you accomplish a number of goals. First, you break down the barriers between buyer and seller, connecting with them on a more human level. You’ll know your audience better—how they think and what they value. Second, you’ll get the rawest type of feedback on your marketing ideas: Will people part with money? Every marketing campaign eventually boils down to an individual transaction. You have a front row seat to how that will happen in practice. Third, you also see group dynamics and influence patterns up close. People are social animals; no buying decision is truly solitary. The specific mechanics of your “club” are less important than the spirit behind it: it’s live and in-person. Instead of laughs (you’ll get some, especially if you’re doing skits), you’re asking for dollars. You’ll learn more in 90 minutes than you could in months of testing.

Rehumanizing Marketing, Chapter 1. Copyright 2018-2024 by Jaywalker Publishing LLC.

Note: This post is part of a serialized publication. Click here to read any sections you missed.